ANDERSONVILLE, GA.

HISTORY

November of 1863 saw Captain W. Sidney Winder of the Confederate Army travel to Andersonville in

Sumter County, Georgia to assess the feasibility of building a prison to hold captured Union soldiers as the

number of Union soldiers being held at Richmond had become too great to handle. Andersonville was

determined to be an attractive site for such a complex because of its location - geographically in the heart of

the deep South, availability of fresh water and close proximity to the Southwestern railroad - and the

elimination of any possibility of resistance from local townspeople (the population of Andersonville was about

20 at that time).

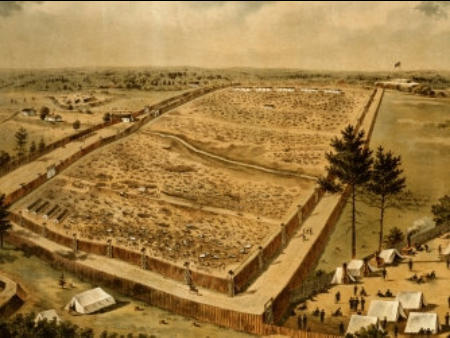

Late the following month, Captain Richard B. Winder arrived in Andersonville to begin construction of the

prison, which was to occupy 16.5 acres and have the capacity to hold 10,000 prisoners of war. The prison was

of a rectangular shape and had a creek flowing through the center. The facility was named Camp Sumter.

One month later in January of 1864, local slaves were brought in to begin clearing the land for the 1010' x

780' stockade. The stockade itself was made from logs of the trees cut down on the site and fit so well together

that they blocked out entirely any daylight from creeping through its cracks. Two gates were constructed on the

west wall and a smaller fence line was built around the inside of the stockade walls about 25' away from those

walls as a sort of "buffer" zone. Prisoners crossing these fences would be shot on sight with no warning.

February of 1864 saw the first Union prisoners arrive and by June of that year the total prison population

had grown to 20,000, double the intended capacity. As a result the prison boundaries were extended 610 feet

to the north, utilizing labor from 100 white and 30 African-American prisoners. The work was completed 14

days later and on July 1 prisoners were then released into the northern extension. By August, the prison

population had grown to 33,000.

Born out of the desperation and struggle for survival, two groups within the prisoner population were

formed: the Raiders and the Regulators. The Raiders were a predatory group of prisoners who would assault

and rob fellow soldiers in order to meet their own survival needs. The Regulators were formed to combat these

renegade prisoners. Regulators would eventually capture and take to trial those who committed these crimes

against their "own". The Raiders were convicted and sentenced to be hung while others were given lesser

punishments and allowed to live.

As Union raids were a constant threat, a 12' high middle and a 5' high (never completed) outer stockade

fence was built around the main perimeter. Earthworks commenced with the construction of Fort Star

southwest of the prison, a redoubt northwest of the north gate and six redans.

An overhead sketch of Andersonville Prison

In early September, Gen. Sherman's troops had marched on Georgia and the threat of raids increased,

prompting the transfer of all but about 1,500 prisoners who were deemed to ill to move to other camps in

Georgia and South Carolina. The number of guards also decreased exponentially. Eventually more prisoners

arrived in Andersonville, bringing the population to 5,000 or so, which is what was left of them when the Civil

War finally ended in April of 1865.

The 15-month existence of Andersonville resulted in the deaths of 13,000 Union prisoners by malnutrition,

disease and exposure. In the summer months more than 100 prisoners died per day. All told, over 40% of all

Union prisoners of war who died in captivity expired at Andersonville. While they were to receive the same

rations as their Confederate counterparts, the lack of food available made that all but impossible. The fresh-

water creek that ran through the middle of the camp eventually doubled as a sewer and was cruelly dubbed

"Sweet Water Branch". Prisoners were not allowed shelters and resorted to constructing improvised tents and

fragile lean-tos that left them hopelessly exposed to the elements. Although Union prison camps were as

inhuman and appalling as their Southern equivalents, they were vastly better equipped to handle the crowded

conditions.

Union prisoner at Andersonville - and he survived!

The one saving grace for all prisoners and the last bastion of the hope they had in the goodness of man

came in the form of an Irish immigrant priest named Father Peter Whelan. Fr. Whelan settled first in South

Carolina and then moved to Savannah, Georgia. Each day Fr. Whelan would administer to the captured

troops, many of which were practicing Catholics. Fr. Whelan lived in a small hut about a mile outside the camp

and was the one constant ray of hope in the prisoner's lives. He would offer words of comfort to those suffering

and deliver the last rites to those about to meet their inevitable fate.

Fr. Whelan's kindness and compassion knew no bounds. Once he borrowed $16,000 from a wealthy

Macon, Georgia restaurant owner to purchase 10,000 lbs. of wheat flour which was converted into bread,

which helped feed hungry troops over a four-month period. It was called "Whelan's Bread" by the prisoners.

Even those prisoners not of the Catholic persuasion were given reassurance and solace by the good priest

and many praised him as a saint of sorts in many prisoner's journals that were discovered long after the war

ended. When all but a small percentage of the prisoners were moved to other camps, Fr. Whelan stayed at

Andersonville to tend to those who remained.

The land where some 12,920 prisoners were buried (l.) was designated by the U.S. government as a

National Cemetery. The graves were identified and marked by Clara Barton, founder of The American Red

Cross along with a detachment of soldiers and laborers. In time the land was privately acquired and various

cash crops, including cotton were planted on the site. In 1891 the land was re-acquired by the Grand Army of

the Republic of George and a permanent monument was established at Andersonville Prison (r.).

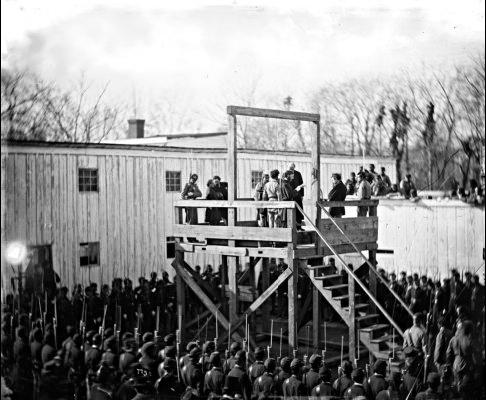

In November of 1865, the commander of the camp, Captain Henry Wirz, was tried and convicted in

Washington D.C. of "impairing the health and destroying the lives of prisoners." He was subsequently hung for

this misdeed in the shadow of the Capital Building (below). Captain Wirz, born in Bavaria, had suffered a badly

damaged arm in battle and was assigned to the prison in March of 1864. By prisoner accounts, he was a cruel

administrator and considered to be an incarnation of the devil himself. In truth, Captain Wirz was at the mercy

of superiors who cared not one iota about the rancid and inhuman conditions prisoners were living under. Any

efforts to improve those circumstances was mainly met with indifference. His refusal of a plea bargain to

implicate Confederate President Jefferson Davis in these crimes assured his execution and he remains the

only man hung for war crimes during the Civil War. Astonishingly, one of people who testified in his behalf at

his trial was none other than Father Peter Whelan.

THE HAUNTINGS AT ANDERSONVILLE

It is theorized that the tormented spirit energy of prisoners who experienced the hopelessness and

suffering of their captivity lives on at Andersonville. Visitors tell tales of gunshots being heard, the sounds of

soldiers marching and the voices of anguish emanating through the prison ruins. The creek that runs through

the camp is an especially active area.

Many apparitions have been said to manifest themselves here. Men in civil war attire have often been

seen, but the two most compelling sightings involve the two men most commonly identified with Andersonville:

Captain Wirz and Father Whelan.

The ghost of Captain Wirz has been frequently seen in the stockade guard tower, as if looking down on

the captive soldiers below. Captain Wirz also is known to haunt the cemetery where his prisoners lay buried.

The spirit of Father Whelan has been seen as a solid figure, thought by some to be a re-enactor of some

kind, but the figure begins to fade and then disappear entirely. A long-time apparition given the name "The

Phantom of Andersonville" is thought by some to be in reality Fr. Whelan himself. The entity is described as

having an extremely large head, a short body, and long arms that hang down to the knees. It is dressed in

dark clothing holding an umbrella over its head as Whelan often did in summer and in rainy weather. A horrible

scent permeates the area when the figure appears.

ANDERSONVILLE PRISON